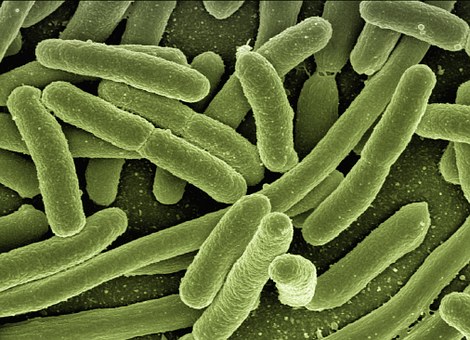

While humans have been eating probiotics by way of cheeses and yogurts for tens of thousands of years, use of supplements for beneficial bacteria is only decades old.

Most studies concentrate on immediate effects of pills and capsules. No reliable data exists on “longer-term consumption” of probiotics, a period of time only now relevant. Thus a new curiosity in the field: how will microbes present when additional probiotics have been used for extended periods?

A little background

Microbial maps are thought to be drawn in early childhood. Being gifted with richly diverse beneficial microbes before and during birth as well as from breast milk is a decided advantage, setting a person up for fewer allergies, autoimmune diseases and metabolic diseases including diabetes and obesity. If probiotics are introduced, there will be transitory change in microbes after which the original template re-emerges when supplements stop.

For example, experiments with Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG demonstrated that the composition of the resident bacterial community in adults remains largely unchanged following probiotic administration.

How would microbes adapt with those taking probiotics for longer periods?

A recent study published in Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins titled Gut Microbiota Alteration after Long-Term Consumption of Probiotics in the Elderly found some interesting results:

Renyuan Gao and colleagues in China found that microbial diversity in the probiotic group was similar to that in the control.

- Certain microbiota were more abundant in the probiotic group however: Blautia, Streptococcus and Enterococcus

- Faecalibacterium, a genus containing anti-inflammatory property, also had a higher abundance in the probiotic group in the gut.

- Also high-dose intake of probiotics resulted in lower microbial richness.

- Inflammatory factor analysis showed that only the level of IL-1β was higher in the probiotic population.

The authors wrote:

“Taken together, our study demonstrated that the long-time intake of probiotics caused significant changes in the gut microbiota structure, including an increase in the composition of beneficial microorganisms, which might contribute to the maintenance of host health and homeostasis of microenvironment. “

What this means as more of us undertake long-term regimens of probiotics will be revealed with more research and frankly how and if we succumb to disease. The microbiota changes with aging and not for the better.

Staving off at least some of the downsides of aging bodies may be a benefit to long-term probiotic use.

Other reading:

In Old Age, Our Altered Microbiomes Can Lead to Disease