written by Susan Hewlings, PhD, RD, Director, Scientific Affairs at Nutrasource – IPA Education & Communication member

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is a term that has gained a lot of traction in most health-related disciplines. It seems like a good idea to make health-related decisions based on scientific evidence whether you are a practitioner or a consumer. What that really means and how exactly to do it is a little less clear. According to Engebretsen et al (2015), the goal of EBM for practitioners is to promote more conscientious and systematic clinical decision making (2). To do so requires interpretation in both individual studies and the scientific knowledge of a given topic as a whole. The precise definition of EBM is not completely agreed upon, however, it involves the integration of (2) clinical experience and expertise; (3) scientific evidence; and (4) patient values and preferences to provide high‐quality services (3). While many professional associations attempt to assimilate scientific information into position stands and guidance, these guidelines can’t cover every clinical topic. Therefore, each practitioner must make their own assessment of the scientific literature. Here we attempt to provide a few tips in assessing a single study but by no means do we cover every aspect in this short paragraph and, while the list was developed with practitioners in mind, it could be applied by the consumer as well. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are generally considered the gold standard for research design, making studies of this nature attractive in making clinical decisions. As outlined by Twells et al. (2015), when assessing a RCT it is important to carefully consider many aspects of the design such as (5):

- What is the research question? Is it described in PICO format? (Population, Intervention, Control, Outcome)

- Is the study design appropriate to answer the question? Were the correct tests used? Did they control for other variables that may have influenced the results (i.e., confounding factors)?

- How did the researchers determine the number of subjects? Was it a power calculation or a convenience sample (i.e., a fraction of a population who they could conveniently have access to)?

- What were the inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting participants? Was the target population you are seeking to apply the results to included or excluded from the study?

- How does the population studied compare to the potential clinical patient(s) in terms of baseline characteristics (i.e., gender, ethnicity, age, lifestyle, etc.)?

- How was blinding (of participants and investigator) and randomization achieved?

- Was an appropriate control arm used?

- How many subjects dropped out and why?

- Were results analyzed per protocol or as intent to treat?

- Is the statistical analysis appropriate to the study design? Was the statistical analysis planned ahead for each outcome?

- What are the main results of the study? How are they presented? (e.g., Relative Risk, Odds Ratio, Hazard Ratio, % change, mean difference, sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios, Number Needed to Treat).

- Are the results provided of clinical importance or just statistically significant?

- Is this the only study that has reported these findings in this population or are there others that support the results?

- Were adverse events and risks reported? Did the authors analyse the generalisability and limitations of their study?

- Was the study registered in a clinical trial registry (and was this done before the study started)?

- For a probiotics study, are the strains properly mentioned?

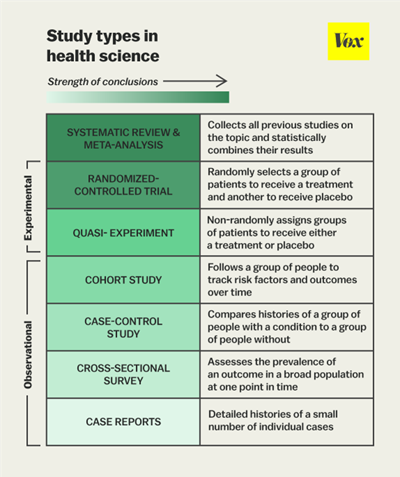

Explained in Figure 1, are the various types of trials and studies of both observational and experimental design (1). Typically, when analysing a given evidence base, the study design dictates the weight of the results in the elaboration of clinical recommendations, although not solely; the abovementioned points have to be assessed for individual studies to estimate the overall significance of the results both clinically and statistically.

Figure 1: Study types in health science (Belluz, J., Hoffman, S., 2015)

When considering the significance of a given result, P values are often used as the only indicator of significance and the validity of such approach is a topic of much debate. The significance of a P value is in fact harder to define than one may think, and some argue that it is overused and misinterpreted. The P value was developed in the 1930s by renowned statistician RA Fisher to quantify the strength of the evidence against the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis is the concept that there is no difference between the factors you are testing, for example your supplement and your placebo, and that the observed difference in your sample population is attributable to chance. The P value is the probability that the null hypothesis is true, so a smaller P value, typically falling below a predetermined threshold, makes it less likely that your result is compatible with the null hypothesis.

A careful review of individual studies or group of studies (i.e., such as in systematic reviews and meta-analyses) is a key element of EBM or evidence-based decision making in general. However, it is important to note that while a careful review of the scientific literature remains critical, the initial EBM definition was extended to integrate clinical expertise and patient-specific needs and values; in other words, it’s the totality of the evidence that must be considered (5).

References

1. Belluz, J., Hoffman, S., 2015 Study types in health science, digital image, VOX, Accessed 29 Nov 2021 https://www.vox.com/2015/1/5/7482871/types-of-study-design

2. Engebretsen E, Vøllestad NK, Wahl AK, Robinson HS, Heggen K. Unpacking the process of interpretation in evidence-based decision making. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(3):529-531. doi:10.1111/jep.12362

3. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996 Jan 13;312(7023):71-2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. PMID: 8555924; PMCID: PMC2349778.

4. Guyatt GH, Haynes RB, Jaeschke RZ, Cook DJ, Green L, Naylor CD, Wilson MC, Richardson WS. Users’ Guides to the Medical Literature: XXV. Evidence-based medicine: principles for applying the Users’ Guides to patient care. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000 Sep 13;284(10):1290-6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.10.1290. PMID: 10979117.

5. Twells LK. Evidence-based decision-making 1: Critical appraisal. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1281:385-96. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2428-8_23. PMID: 25694323.