By Maile Combs, MS, and David Despain, MS

Gut bacteria can influence how you think, feel, or handle stress. Scientists are now exploring how these microbes can affect mood and mental health.

In any given year or at some point during their lifetime, nearly one in five U.S. adults and children are affected by mental health challenges. There isn’t any single cause, as contributors can include levels of stress or underlying biological factors.

When mood and mental health are at risk, common recommendations might include a list of stress-reduction techniques, such as talking with a friend, meditation, getting enough sleep at night, or engaging in physical activity.

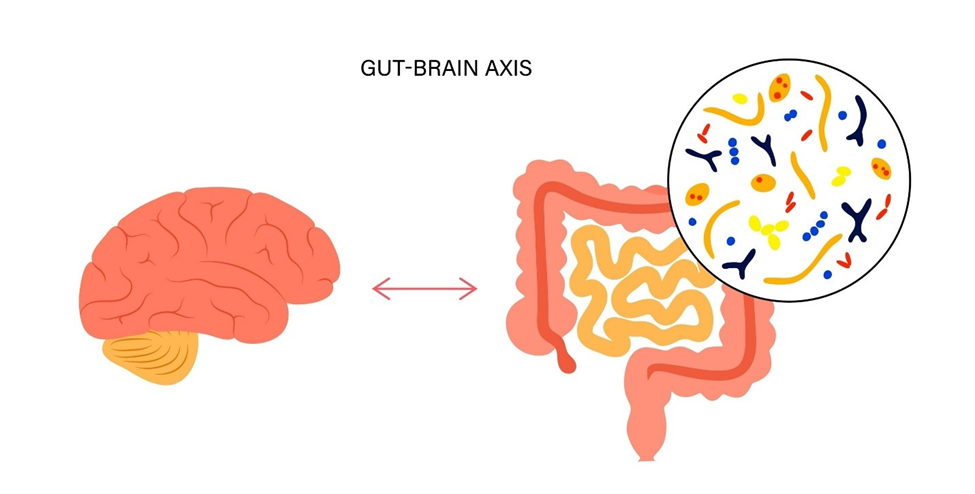

Less well known is that anxiety and stress could have origins in the gut. The connection between brain and gut is well established, often referred to as the “gut-brain axis,” with a basis in research that a person’s mental state or emotions can affect their digestion or vice versa (see sidebar).1,2 This “gut-brain axis” is now understood to originate from bidirectional communication between the brain and nerve cells that line the gastrointestinal tract, by way of the vagus nerve.2

Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis

More recently, research has turned its focus toward the influence of microbes on the gut and brain, expanding the relationship to a “microbiota-gut-brain axis.”1,3-8 These microbes, their species diversity and their populations inside our guts are heavily influenced by dietary factors, such as our intake of fermented foods and prebiotic-rich whole grains, fruits and vegetables.9

Gut microbes produce metabolites, like short-chain fatty acids, neurotransmitter precursors, and vitamins, that travel through neural and circulatory pathways. Based on these metabolites, gut microbes are gaining recognition for their apparent effects across the entirety of the body, including the brain and influencing responses to stress and anxiety.10 While not fully understood, recent observational and clinical studies have offered us a glimpse into how gut microbes could influence intestinal neural cells directly to affect mood and mental state.8

Microbiota Dynamics, Mental Health, and Therapeutic Futures

New research continues to mount in the quest to understand what an optimum microbiota looks like, and exactly how changes and timing have an impact on the brain. The primary goals are to identify strategies to shape the microbiota for optimal brain development and function throughout life.

Much of our knowledge about gut microbes comes only from observational studies. However, it’s becoming increasingly clear that there exist specific windows where infant and child brain development coincides with development of the gut microbiota.

These conclusions are based on associations between gut microbiota and cognitive outcomes from fine motor skills to social interactions, temperament, fear response and stress coping.11 Sex may also play a role. For example, certain bacterial abundances are associated with extroversion in boys only, while microbiota compositions correlate with fear reactivity only in girls.11

Emerging research suggests that adopting strategies to guide microbiota development or promote its positive change may directly or indirectly influence brain structure and function for mental and emotional well-being. These microbial shaping interventions could include one or more of the following strategies:

- Provision of specific nutrients, or prebiotics, for targeted modification

- Transplantation of whole microbial communities from a healthy donor

- Addition of beneficial microbes in the form of probiotics

Some promising results have been seen in preliminary animal studies. For example, rodents with absent or altered gut microbiota are observed to have blood-brain-barrier dysfunction and mental deficits that can be mitigated by replenishing beneficial microbes.10

In middle-aged and elderly humans, including those with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease, studies have explored microbiota-gut-brain axis therapies to alleviate symptoms of cognitive impairment, depression, and anxiety.7,8 Additional research has sought to find innovative therapies, such as supplementation or fecal microbial transplants, that might contribute to healthy child brain development with effects on learning and memory.7

For the moment, many of the most pressing research questions remain unanswered. It’s still too early to know if resulting discoveries will bring life-changing results. The science centered around the microbiota-gut-brain axis is new and incredibly complex, yet exciting, as studies continue to uncover more links that could lead to improved mental health for the future.

Side bar: What is the gut-brain-axis? A little history…

In 1822, Canadian fur trader Alexis St. Martin made medical history after he was accidentally shot in the stomach at close range. He lived, but with a gaping hole in his gut that never fully healed. This allowed his doctor to study his digestive process by inserting food, then removing it for analysis after partial digestion. His doctor also observed for the first time that emotions and mental states like anger or irritability affected his digestion rate, making one of the first inferences of a gut-brain connection.

By the 1980s, the advent of brain imaging technology would provide a more accurate picture of the two-way street in which the brain and gut affect each other. This bidirectional pathway is composed of the central, enteric, and autonomic nervous systems.

Hundreds of millions of neurons within the gastrointestinal tract make up the enteric nervous system, which is often described as the body’s “second brain.” Other cells within the GI tract produce around 90 percent of the body’s neurotransmitter, serotonin, which among other functions is known as the brain’s “feel good” chemical.

Part of the autonomic nervous system, the vagus nerve extends from the brain to the abdomen and regulates all the body’s involuntary processes including eating, swallowing, digestion and movement of food through the GI tract. The vagus nerve is also influenced by food and is often implicated in common digestive disorders like irritable bowel syndrome.12

Added to the mix are new studies evaluating how gut microbes influence the gut and brain. The latest research suggests that eating a balanced diet containing fiber-rich fruits and vegetables along with fermented foods, such as kefir or sauerkraut, could contribute to lower perceived stress levels.9

References

- Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;7:124-136. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29276734/

- Cryan JF, O’Riordan KJ, Cowan CSM, et al. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Physiol Rev. 2019;99(4):1877-2013. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31460832/

- Kelly JR, Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Brain-gut-microbiota axis: challenges for translation in psychiatry. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(5):366-372. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27005587/

- Gambaro E, Gramaglia C, Baldon G, et al. “Gut-brain axis”: Review of the role of the probiotics in anxiety and depressive disorders. Brain Behav. 2020;10(10):e01803. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/brb3.1803

- Hayes CL, Peters BJ, Foster JA. Microbes and mental health: Can the microbiome help explain clinical heterogeneity in psychiatry? Front Neuroendocrinol. 2020;58:100849. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32497560/

- Gershon MD, Margolis KG. The gut, its microbiome, and the brain: connections and communications. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(18). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34523615/

- Baldi S, Mundula T, Nannini G, Amedei A. Microbiota shaping – the effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and fecal microbiota transplant on cognitive functions: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(39):6715-6732. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34754163/

- Chakrabarti A, Geurts L, Hoyles L, et al. The microbiota-gut-brain axis: pathways to better brain health. Perspectives on what we know, what we need to investigate and how to put knowledge into practice. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(2):80. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35044528/

- Berding K, Bastiaanssen TFS, Moloney GM, et al. Feed your microbes to deal with stress: a psychobiotic diet impacts microbial stability and perceived stress in a healthy adult population. Mol Psychiatry. 2022. Available at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-022-01817-y

- Parker A, Fonseca S, Carding SR. Gut microbes and metabolites as modulators of blood-brain barrier integrity and brain health. Gut Microbes. 2020;11(2):135-157. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31368397/

- Vaher K, Bogaert D, Richardson H, Boardman JP. Microbiome-gut-brain axis in brain development, cognition and behavior during infancy and early childhood. Developmental Review. 2022;66. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0273229722000284

- Breit S, Kupferberg A, Rogler G, Hasler G. Vagus Nerve as Modulator of the Brain-Gut Axis in Psychiatric and Inflammatory Disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:44. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00044/full

Authors

Maile Combs is Senior Manager, Medical Affairs for Nestlé Health Science, where she oversees nutritional science support for many of the company’s dietary supplements. Maile has spent more than two decades in the supplement industry with a special focus on driving growth in the probiotic and gut health categories through consumer relevant communications and substantiating the safety and efficacy of emerging probiotic ingredients for new products. Maile holds a BS in Analytical Chemistry from Northern Arizona University, and a MS in Human Nutrition from the University of Bridgeport. Maile lives with her husband Jeff in Prescott, Arizona.

David Despain is Director, Nutrition Science and Communications, at Nestlé Health Science. In his role, he fosters greater communication within R&D with a focus on advancing the development of nutritional product innovations. David has a BA in English from University of Illinois at Springfield, a MS in Human Nutrition from the University of Bridgeport, and is a Certified Food Scientist with the Institute of Food Technologists. He is also currently pursuing a MS in Science Communications from Stony Brook University. David lives with his wife Patricia in Centereach (on Long Island), New York